Mamma and Pappa lived down on the bayou

Little bitty house-boat all alone

Seven years of marriage they produce no children

So Pappa started thinking bout a Cajun clone

Five scientists come to the Loozeyanna Bayou

Tell my Pappa that a son would be born

So they built them a lab in the swamp with the gators

And there they made me, a little Cajun clone

CHORUS:

I'm a Cajun clone, a Cajun clone

I'm just like my Pappa way down to the bone

You can look under cabbage leaf, look under stone

Look for me, you find a Cajun clone

Well they call Pappa "Louie" and my Mamma "Marie"

I got 12 baby brothers, look a just like me

Word got out and it didn't take long

And now the whole damned bayou's full of Cajun clones

(Repeat Chorus)

copyright Sidhe Gorm Music (BMI)

(written 1978)

It was a muggy August morning in Lake Charles, Louisiana back in 1975 as I stood out on a shoulder of I-10 with my thumb out looking for a ride. This was my second and, as it turned out, my last great hitchhiking trip.

My destination was Birmingham, Alabama but I’d decided to check out the great city of New Orleans before I got there. I’d stopped to spend the night in a motel in Lake Charles after a rough and hungover day of hitchhiking from Austin, Texas the day before.

Luckily, I didn’t have to wait long for a ride that morning. Within a few minutes, a white station wagon pulled over for me.

The driver was a guy with a smiling face, jet black hair and a straw cowboy hat, whose brim curved down as if to follow his long nose.

He looked familiar.

And when I told him I was headed to New Orleans, the talk turned to music. Specifically Cajun music, the music he’d grown up on.

“When I was a kid, my parents and my grandparents used to have these big parties. Everyone came,” he said with a thick Cajun accent.

“And after a while, everyone would bring out their instruments and they would BOOGIE!”

By that point, I realized who this driver reminded me of: He was a dead ringer for Doug Kershaw, the Cajun singer/fiddler whose rocking album Alive & Pickin’ I’d been listening to for months before my trip.

Though he had to turn off and let me out long before I reached New Orleans, this guy – his accent, his pride in his culture and his face – stuck in my memory. I wanted to go to one of those parties with his parents and grandparents, which I’m sure had plenty of jambalaya and crawfish pie.

And even though it would have been way too big of a coincidence for him to have actually been Doug Kershaw, the strong resemblance made me wonder.

And describing him to a friend later I jokingly said, “Maybe he was a Cajun clone …”

Contemplate that while listening to Doug Kershaw’s best-known song, played here with his late brother Rusty Kershaw in 1961:

Obviously “Cajun Clones” was a loving tribute to Doug Kershaw and “Louisiana Man.”

I guess you can consider my song to be a “parody” though unlike the works of, say Alan Sherman or “Weird” Al Yankovic, my song doesn’t use the actual melody of an existing song. (I can’t say the same about “Solar Broken Home,” which I’ll discuss in an upcoming chapter.) “Cajun Clones” is more of a genre parody.

Not to mention, both Alan’s and Al’s normal parodies were of very popular tunes by very famous artists. Mine tended to be far more esoteric. I had the uncanny knack of parodying music that was mostly unknown to the mainstream.

So, unfortunately, when I tried to explain I was poking a little fun at Doug Kershaw, far too many people would reply “Who?”

Weird Al never had that problem with Madonna or Michael Jackson.

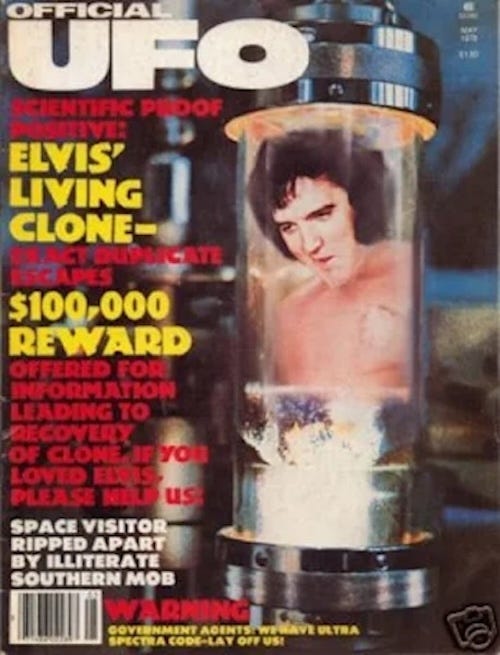

Besides the Kershaw influence, there was this idea of cloning that was becoming more popular in the public imagination in the 1970s.

Even Elvis reportedly was cloned before his death.

Biologists had been experimenting for decades with techniques that would lead to what we call cloning. And science fiction writers going back at least as far as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1931), dealt with dystopian worlds with human cloning.

But the 1970s was a fertile period for cloning in popular culture. There were movies like Woody Allen’s comedy Sleeper (1973); a lesser-known film called The Clones that same year; the original version of The Island of Dr. Moreau (1977) and The Boys from Brazil (1978).

And this is when the idea of cloning started creeping into music.

George Clinton’s Parliament released their 1975 classic The Clones of Dr. Funkenstein.

Pat Benetar’s 1979 debut album In the Heat of The Night had a little-known deep cut called “My Clone Sleeps Alone":

You know and I know, my clone sleeps alone

She's out on her own, forever

She's programmed to work hard, she's never profane

She won't go insane, not ever

Just slightly this side of the ‘70s, Alice Cooper couldn’t resist the fun with his 1980 tune “Clone (We’re All)” that begins “I'm a clone, I know it and I'm fine/ I'm one and more are on the way.”

But my favorite was The Tubes’ “Cathy’s Clone” from 1978. It featured Captain Beefheart on sax.

I don’t think Don & Phil done it this way:

So from this milieu sprang “Cajun Clones.”

I don’t remember exactly when or where I wrote “Cajun Clones.” But I do know it was part of my repertoire in my early days of performing in the mid-late ‘70s. It always was a crowd-pleasure and one of my major request-getters during my years of Sunday night Forge shows.

Usually when I did it live, after the first chorus, I’d do a little schtick. Taking the guise of some imaginary snooty music ethnologist, I’d say something like “And now, ladies and gentlemen, for your listening pleasure I’d like to demonstrate an authentic Cajun holler.”

Then I’d unleash a bloodcurdling scream that no self-respecting Cajun – or any other sane person – would ever want to claim. This usually would result in laughs, and many times, startled gasps from first-timers.

By the time we were planning go to the studio, I knew I’d want some country and Cajun elements on this track. So, in addition to Tom Dillon on steel guitar, I recruited a couple of friends of mine who had moved to New Mexico from Louisiana bayou country a couple of years before, Jeanie McLerie (RIP) and her husband Ken Keppeler.

I first met Ken and Jeanie when they lived in Santa Fe about a year before we recorded Potatoheads. They were playing around town as a duo they called “Bayou Ken & Zydeco Mouton.” I was assigned by the Santa Fe Reporter to write profile of them, so I went to one of their gigs at a some little café that no longer exists.

Besides admiring their talent, I liked them both instantly and we became friends. I remember them coming to my house for dinner one night and afterwards playing music – me struggling not to screw up their songs with my limited abilities on guitar.

I remember my infant daughter listening intently to this music in our living room and me thinking how lucky she was to grow up in a house full of music. (I’ve asked Molly, and no, she doesn’t remember that night.)

Jeanie and Ken were living in Albuquerque by the time we recorded my album. A few years later they moved to Silver City, N.M., where they became known for their band Bayou Seco.

Here’s Bayou Seco playing “Bosco Stomp”:

Both Jeanie and Ken played fiddle on “Cajun Clones.” They stuck around after we recorded their parts for that song to lend their craft to the song “Potatoheads’ Picnic,” Jeanie staying on fiddle, Ken switching to accordion. (More on that tune in an upcoming chapter.)

Ken told me that he was disappointed in the mix when Potatoheads was released later that year. He told me the fiddles were mixed too low and after re-listening. I assume Jeanie felt the same way.

I had to agree.

So when we remixed the album in the mid ‘90s for the CD version, I made sure those Cajun fiddles were more prominent.

And that’s the mix you’ll hear below.

And now, enjoy my song:

Credits:

Steve Terrell, lead vocals, acoustic rhythm guitar

Jack Clift: lead guitar, producer

Mike Roybal: bass

David Valdez: drums

Tom Dillon: Steel guitar

Jeanie McLerie: fiddle

Ken Keppeler: fiddle

Get your own copy of Picnic Time for Potatoheads & Best-Loved Songs from Pandemonium Jukebox HERE