When I was a young boy I saw things different

I could see the spirits in the air

I Knew my real Pa he was Apache

And I knew I was a brother to the bear

xx

At the age of seven I started running’

I’d run away upon to the woods

And them voices they just a kept a gettin’ louder

By the age of 12 I had left home for good

BRIDGE

Up to the mountains of Montana

I learned to live beneath the trees

I felt the changin’ of each season

The deer, the wolf, the bear and me

x

I left Montana and joined the Army

The wind led me to battles far away

My Apache blood made me a mighty warrior

The bear in me grew stronger every day.

x

Back in the States I became a drifter

’Til I met a girl, who was as pretty as a song

First time I ever knew my soul felt easy

But that goddamn bitch she went and did me wrong

BRIDGE

I did not know what I was doing

I was just like a wounded bear

Cop crossed my path and I blew his fucking head off

And that is how I ended here

But sometimes I leave this dirty prison

And I can smell the mountain air

Montana moon still shining’ cup above me

And I’m still brother to the bear

copyright Sidhe Gorm Music (BMI)

(written 1983)

Ripped from the headlines!

That’s how you could describe "Brother to the Bear." I’m pretty sure this is the very first song I ever wrote — and definitely the first, in fact, only one I ever recorded — that was based on a newspaper story I’ve written.

The murder described in the story actually happened and the details are how the killer in the song actually described them to me — though, reading up on his case years later, there are some details he left out.

Here’s how everything came about:

In late July of 1982, I dropped by the office of The Santa Fe Reporter. This was nearly a year before I started working full time there, but I’d been freelancing for a couple of years at the Reporter. For several months by that time, I had a weekly column called Santa Fe Notebook.

That was a fun column, which often became cover stories for the weekly paper. I tried to focus on interesting, oddball characters around the Santa Fe area.

For instance:

One week my column was about a guy who lived in a Pacheco Street storage locker. When I went there for the interview, he greeted me with a rifle pointed straight at me. I talked him out of shooting and proceeded to interview him. But after that story was published, I got a call from a concerned librarian who told me some crazy guy was there at the downtown library madly Xeroxing my column and mumbling about murdering Steve Terrell. Fortunately I never ran into him again.

I wrote about a lady whose daily mission was to go around to prairie dog holes in vacant lots and leave bunches of vegetables. In the course of the interview I learned that this woman briefly had been married to one of my favorite uncles.

I interviewed a trio of self-described winos (two of whom were regular members of my Sunday night crowd at The Forge.) In that column I quoted Roger Miller’s "King of the Road," pointing out that these guys knew "every lock that ain’t locked when no one’s around." A couple of weeks later I later ran into Roger, who lived in Tesuque, N.M. at the time. He said he loved that column adding, "I would have loved to have been with you when you interviewed those guys!" I’ve treasured that remark more than any journalism prize I ever won.

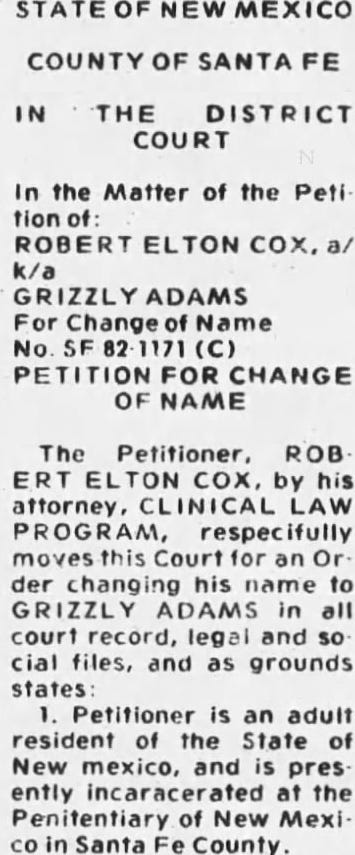

On that day in July 1982, the late Dick McCord, who was editor and co-founder of The Reporter approached me with the classified section of The Santa Fe New Mexican (my future employer for more than three decades.)

"I think this could be a fun column," he said, showing me a legal ad.

It looked like this:

It was a notice for a petition for a legal name change.

Reading through the legal gobbly gook, I learned it filed by a prison inmate, one Robert Elton Cox.

Cox wanted to change his name to that of a popular TV character in the late 1970s, played by actor Dan Haggerty. The tv show was based on a 1974 movie which was (very loosely) based on the life of a California mountain man and circus bear trainer who was a distant relative of two U.S. presidents .

Anyone remember Grizzly Adams?

According to the legal notice, Cox said he "desired to acknowledge the heritage of his past as an Indian and a mountain man" but that desire was hindered by his birth name, "as he is classified as an Anglo-Saxon, contrary to his heritage."

Cox also "desires to fortify his acceptance of his race and his religious faith as an Indian by taking the name of the family his father and deceased relatives."

So I agreed with Dick. This would be a fun column!

So I arranged with the state Department of Corrections to contact the man who wante to be called "Grizzly" and get on his approved visitors list and arrange for an interview at the then-new Central New Mexico Correctional Facility in Los Lunas.

And, doing some preliminary research I learned why he was in prison: He had killed a Lincoln County sheriff’s deputy named Tommy Bedford in Nogal Canyon not quite three years before.

This might be good for a music break. Here’s Southern Culture on the Skids:

Before driving down to Los Lunas that day, the only time I’d set foot inside a prison was one night back in high school when, for reasons I’ve forgotten, my speech class went to the main penitentiary to join some class.

I don’t remember much about that night. Maybe some of our dramatic interpretation kids did some brief performances. I mostly remember us talking with the inmates in the class. They seemed happy that we came out there to be with them for an hour or so.

And that’s how I found Grizzly in 1982.

As I wrote at the time:

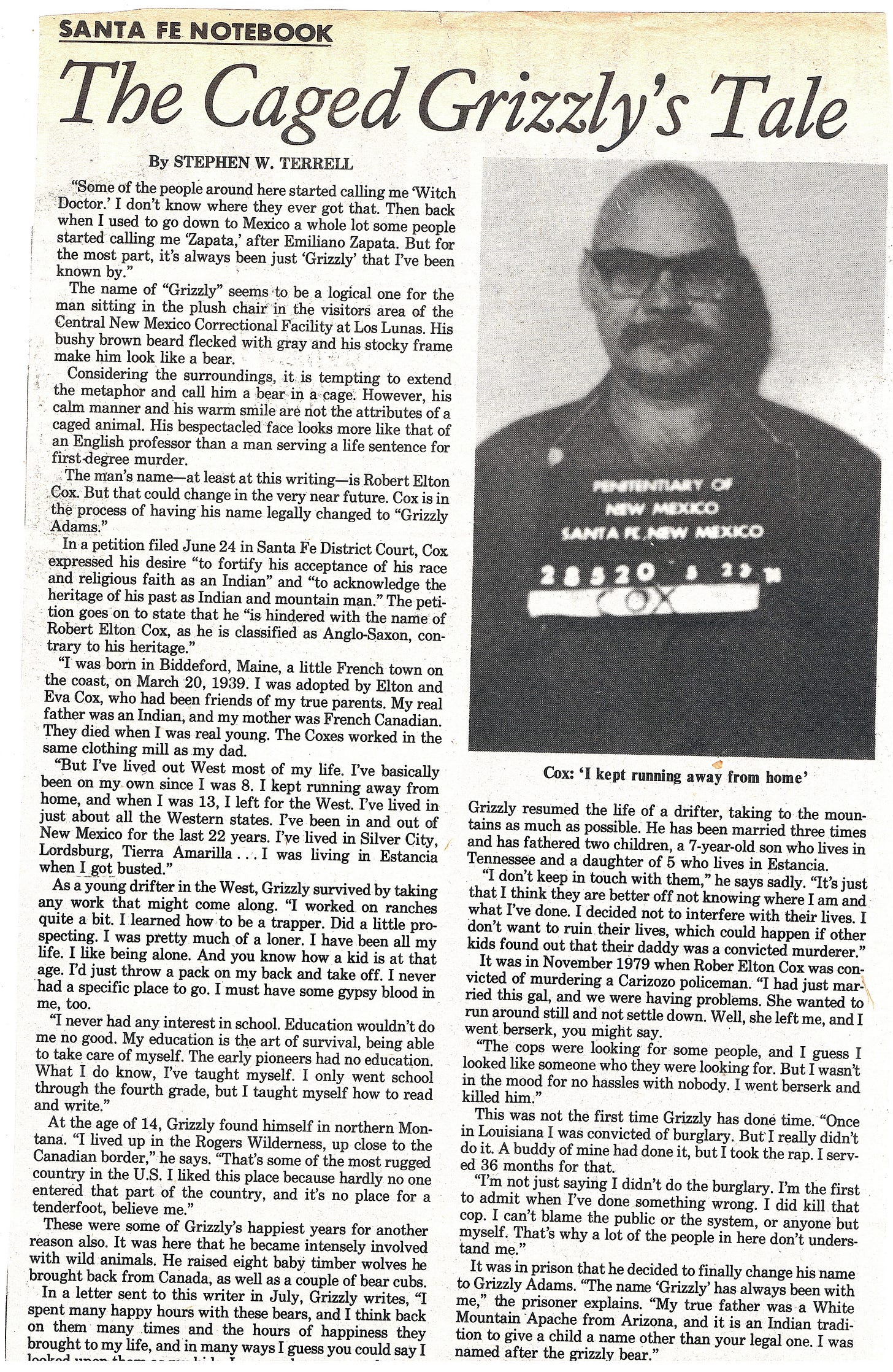

The name of `Grizzly’ seems to be a logical one for the man sitting in the plush chair in the visitors area of the Central New Mexico Correctional Facility at Los Lunas. His bushy brown beard flecked with gray and his stocky frame make him look like a bear.

Considering the surroundings, it is tempting to extend the metaphor and call him a bear in a cage. However, his calm manner and his warm smile are not the attributes of a caged animal. His bespectacled face looks more like that of an English professor than a man serving a life sentence for first degree murder.

But Grizzly wasn’t any English professor. He told me of his hardscrabble life, growing up in rural Maine.

Born in 1939, he said his birth parents had been killed in an accident when he was very young and he’d been adopted by the Cox family. His adoptive parents worked in a clothing mill with his father, who, Grizzly claimed, was a White Mountain Apache from Arizona.

As with much of what Grizzly told me about his early life, I couldn’t verify this. But it was the story he wanted to lay out for his court case.

"I’ve basically been on my own since I was 8," he told me. "I kept running away from home, and when I was 13, I left for the West. I've lived in just about all the Western states."

The place he seemed to love the most was northern Montana.

"I lived up in the Rogers Wilderness, up close to the Canadian border," he told me "That's some of the most rugged country in the U.S. I liked this place because hardly no one entered that part of the country, and it's no place for a tenderfoot, believe me."

Grizzly told me that during this time he raised eight baby timber wolves he’d brought back from Canada. He also said he’d raised two bear cubs during this time.

He spoke lovingly of his relationship with wild animals. "I just love animals," he told me. "They understand me and I understand them."

He told me he enlisted in the Army in the late 1950s, saying he’d been an Army paratrooper stationed at Jackson, South Carolina. And after that, he claimed, he became a mercenary in Central America and Africa.

Grizzly said he’d been married three times and had two children, a son, age 7, and a daughter, who was 5 at the time. However he said he was not in touch with either. "It’s just that I think they are better off not knowing where I am and what I’ve done."

I asked him about the murder of Deputy Bedford. He just gave me a brief sketch of the crime. "I had just married this gal and we were having problems," he said. "She wanted to run around still and not settle down. Well, she left me and I went berserk, you might say.

"The cops were looking for some people and I guess I looked like someone who they were looking for. But I wasn’t in the mood for no hassles with nobody. I went berserk and killed him."

Grizzly, in our interview, left out many details about what led up to the murder.

According to 1979 news reports, he and a 16-year-old boy were implicated in a string of burglaries in Lincoln county and an auto theft in Albuquerque. The discovery of the stolen car led Bedford and other officers to Nogal Canyon on Monday, Oct. 8, 1979.

At one point, Bedford called his dispatcher to report he was stopping a couple of hitchhikers, one of whom had a weapon. That was the last time anyone, besides those hitchhikers, heard his voice.

Bedford was shot five times.

A massive manhunt ensued. First, the next day, the teenager was captured, then, on the Friday after the killing, police finally located Grizzly, carrying a bag of groceries on a road in Corona, N.M. He surrendered without incident.

"I’m the first to admit when I’ve done something wrong," he said. "I did kill that cop. I can’t blame the public or the system or anyone but myself. That’s why a lot of people in here don’t understand me."

Just a couple of weeks after his arrest, Grizzly pleaded no contest to first-degree murder. In doing so, he escaped a possible death sentence.

Shortly after my Reporter story was published, a judge denied Grizzly’s name-change petition.

Grizzley and I stayed in touch — “pen pals,” pun acknowledged — for probably about a year. An enthusiastic woodworker, the next Christmas he made my daughter a wooden “rock-a-duck” (like a rocking horse, but instead shaped like a duck) for her second Christmas.

But at some point we lost touch. It’s probably my fault. I had a new job, a young daughter and a deteriorating marriage that took up up so much time and energy. The letters to and from Grizzly became less and less frequent until they eventually just stopped.

Once in the late 1980s or early ‘90s, after being transferred from the Los Lunas prison to the Santa Fe pen, he was injured in some kind of attack. I tried to visit him while he was hospitalized at St. Vincent Hospital. But the corrections officers guarding his room wouldn’t let me in.

A few months after our 1982 interview, I wrote “Brother to the Bear.”

I didn’t want to portray Grizzly as a victim who was facing unjust persecution, as Bob Dylan did with Ruben “Hurricane” Carter. And I certainly didn’t want to portray him as a hero.

Both Grizzly and I knew this would be false and cheesy.

Instead, I wanted to capture the sadness of Grizzly’s story.

I wanted a mournful, minor folk-style murder ballad about a misfit who “saw things different,” who was on the run for most of his life before prison. A guy who could turn to his cherished memories of roaming the mountains, living “beneath the trees,” whenever he needed to transcend “this dirty prison.”

When Tom Dillon and I recorded it a year or so later — Tom adding some haunting steel guitar and a stinging electric guitar solo — I realized that this would be the first and arguably the only humor-free song I’d ever put to tape.

(“The Mushroom Sweet,” which I’ll discuss next week, ain’t exactly a knee-slapper either. But the psychedelic excess in that tune still makes me grin.)

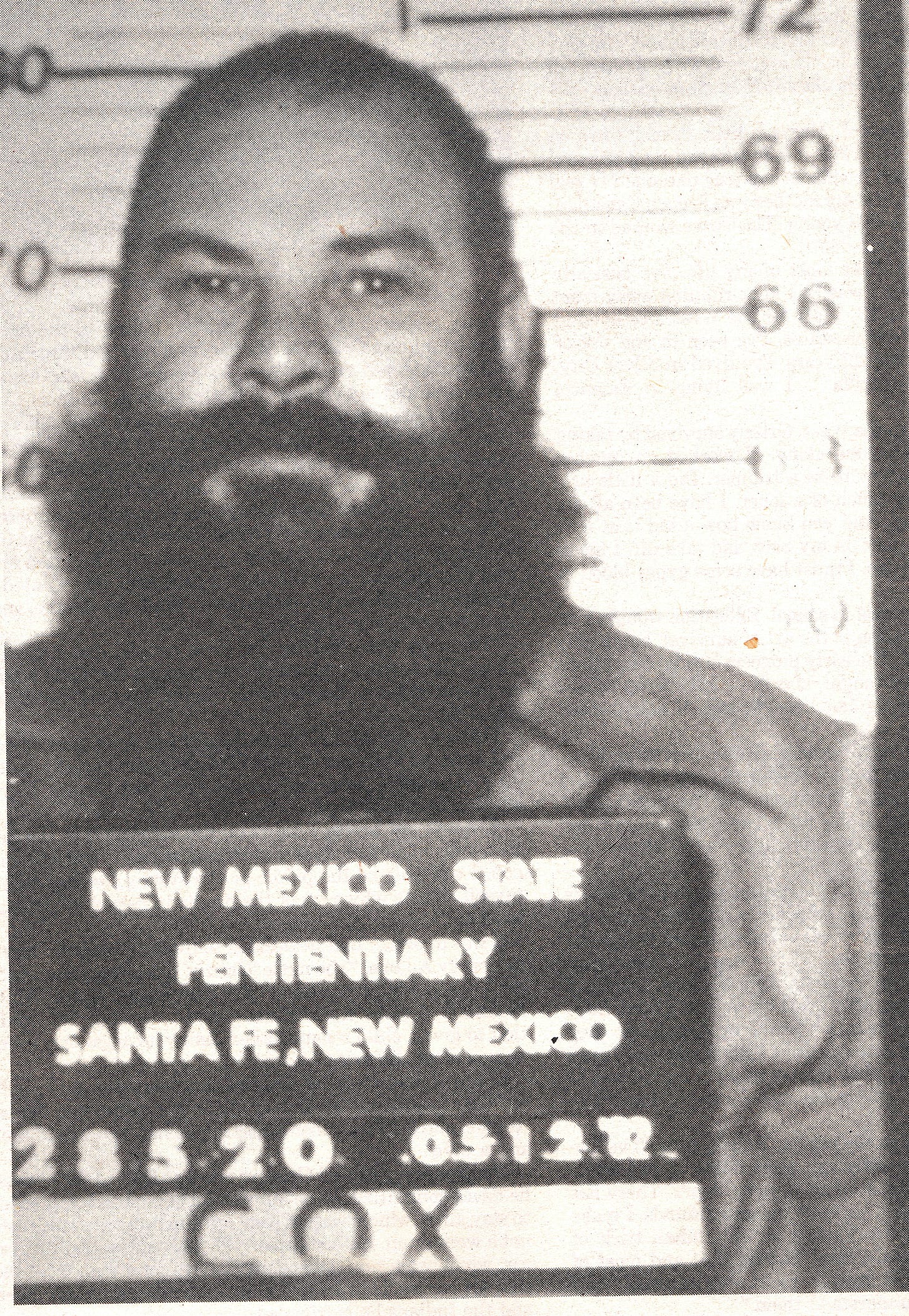

I regret losing touch with Grizzley all those years ago. He died in prison in December 2022.

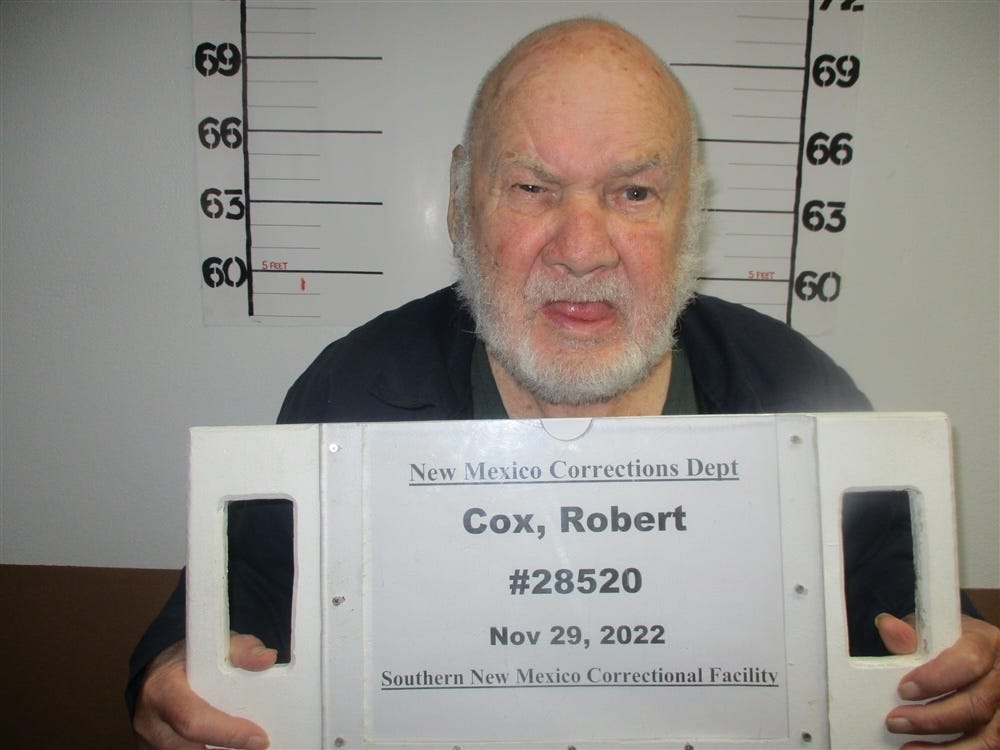

Here’s a prison mug taken just weeks before he died:

So, for the second week in a row, I’m ending on a rather depressing note.

But once again, I’ll stay true to the Wild Spuds format. So …

Now enjoy my song:

Get your own copy of Picnic Time for Potatoheads & Best-Loved auSongs from Pandemonium Jukebox HERE

Credits:

Steve Terrell: lead vocals, acoustic rhythm guitar

Tom Dillon: electric guitar, pedal steel guitar